Livestock

Livestock presents its own unique challenges. All animals require your care and attention, knowledge of the diseases and how to treat them, breeding and weaning, hoof maintenance if applicable and the best feed and forage for each. Before you buy your first animal, determine if your land is suitable for livestock. Poorly drained soil and swampy ground is not. Prepare your land by planting perennial pasture on slopes to provide a good use for steep land rather than using it for annual crops, since annual crops often require tilling that will cause soil erosion. Be sure to find a recommended veterinarian ahead of time. Always have the infrastructure and knowledge before getting livestock – facilities, fences, water, an understanding of their habits and needs. Start small with livestock and make small mistakes. These animals are in your care.

We strongly recommend working alongside a livestock farmer or rancher before deciding if livestock is right for you and your land. And remember the standard wisdom on the height of forage when determining when to move your animals: take half, leave half.

Common Threat

Disease, escaping livestock, predators (raptors, coyotes).

Best Management

Rotational grazing, watering, seeding forage.

Common Capital Expense

Building and moving fences, processing or bringing animal to processing facility, feeding.

Common Labor Expenses

Fencing, feed (hay and grains), seeding pasture, infrastructure (depending on animal), watering systems.

Landowners Lessons

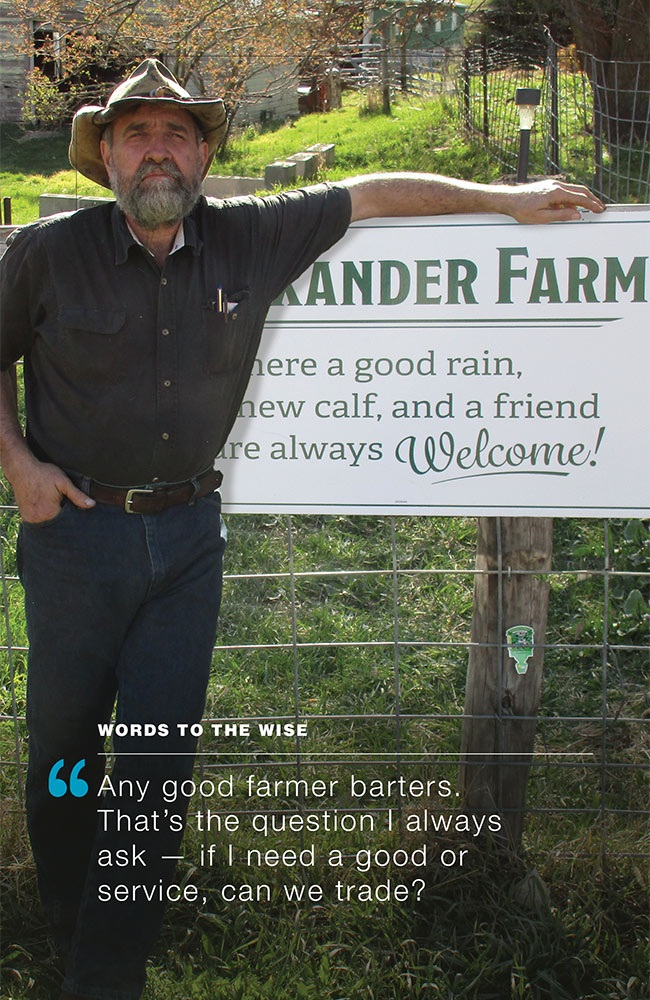

KIM ALEXANDER

My parents bought this farm in the Loess Hills of western Iowa back in 1961, a few years after they bought their first farm a mile away. Dad believed and did everything the USDA, ISU and county extension told him about farming, probably because his father died in a farm accident when Dad was young and he didn’t know any better. This meant, “Goodbye self-sufficient farming” and “Hello, ‘Get big or get out,’” leveraging owned land to buy more land, planting fencerow to fencerow and getting rid of the livestock. When the 1980s Farm Crisis hit, my folks had to sell their machinery to repay the bank, but managed to hang onto some land through Chapter 13 bankruptcy, the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and working off-farm jobs. When Dad went broke, he grew only corn and beans. These hills weren’t made for corn and beans. They were made for grazing livestock on perennial grasses.

With the farm taken out of production there was no place to farm, so in the mid-80s my immediate family moved to Texas and I learned Farming 2.0. We followed Joel Salatin’s models and did pastured eggs, broilers, turkeys — all with on-farm processing and direct marketing — as well as grass-finished beef. When Dad passed away, Mom sold us this 160-acre farm on contract. I was 54 when I migrated back. The buildings were run down, fields had grown up to brush and trees. The farm was sadly neglected. Working an off-farm job helped pay for this place until I got the production up and running.

Now it’s highly productive, organically farmed, diversified, self-sufficient, and able to weather any economic upheaval. It is very stable ecologically, financially, socially and spiritually; an oasis of life in the midst of a corn and soybean desert. If you farm with nature instead of against it, you find the production systems put in place are forgiving and resilient, instead of always feeling like you’re right on the edge of an ecological or financial cliff.

This is agriculture, not agribusiness. It is what farming was throughout time immemorial — growing food for people to eat. So, “I eat all I can, can all I can’t and sell all I can’t can.”